MOMEMTUM by A.D. Cook, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 48″ x 120″

Interview by Robert Maxhimer, Director of Collections and Exhibitions, National Corvette Museum, Bowling Green, KY.

Interview by Robert Maxhimer, Director of Collections and Exhibitions, National Corvette Museum, Bowling Green, KY.

“The object of art is not to reproduce reality, but to create a reality of the same intensity.”

— Alberto Giacometti

With the advent and rapid evolution of artificial intelligence over the previous few years, an existential debate has been born with one area of our reality at the center: creativity. AI has forced us as a society to come to terms with what it means to create and celebrate art in all its forms. Specifically, art is viewed as an inherently human medium of expression. If a program helps to fill in the blanks or even create an artwork all on its own and is devoid of consciousness or emotion, can we then have it be considered “art” at all?

With the advent and rapid evolution of artificial intelligence over the previous few years, an existential debate has been born with one area of our reality at the center: creativity. AI has forced us as a society to come to terms with what it means to create and celebrate art in all its forms. Specifically, art is viewed as an inherently human medium of expression. If a program helps to fill in the blanks or even create an artwork all on its own and is devoid of consciousness or emotion, can we then have it be considered “art” at all?

As AI technology continues to advance, it is becoming increasingly difficult to differentiate between the reality of what is organically created or mechanically manufactured.

Long before artificial intelligence consumed all conversations related to the blurred line of assisted creativity, artists had often found themselves at the center of the question, “How is art defined?” Art, whether a sculpture, painting, photograph, theatrical production, or film, is inherently subjective and interpreted only through the eyes of the individual viewing it at that given moment. The viewer consumes and digests the art, not as a computer program might with cold ones and zeros, but through the filter of their memories, experiences, and opinions formed over many years or seconds before their eyes reach the canvas.

A key element of the art debate is defining the objective of art in our culture. Is art a means to escape the reality we live in the day-to-day, a way to see an object or landscape that would otherwise be foreign to us or is the objective to bend reality into a world of surrealism? The debate has been ongoing since the time of Aristotle in ancient Greece, who believed “… art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” This directly contradicts the works produced by Rembrandt or Vermeer, who were dedicated to realism in portraiture. These paintings, along with the Mona Lisa or still life works from Caravaggio and Adriaen van der Spelt, aim to reflect life at such a hyper-realistic quality that it draws the viewer to a time, feeling, or emotion captured forever on canvas. You cannot help but be in awe of the dedication and discipline required to achieve this level of artistic ability. Still, it is precisely because of this ability and discipline that you are forced to focus on art, not the artists themselves.

“Art is not freedom from discipline, but disciplined freedom.”

— John F. Kennedy

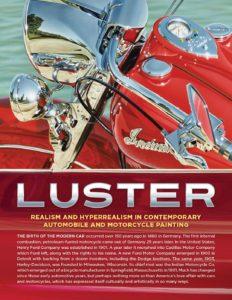

Although most of the art referenced above was produced in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and contributed to the Baroque movement, the core of that movement has evolved and manifested itself in many areas of the art world today. A new movement, hyperrealism, is at the center of an exhibition recently premiered at the National Corvette Museum. Occupying the newly renovated Limited Engagement Gallery, Luster: Realism and Hyperrealism in Contemporary Automobile and Motorcycle Painting takes its cues from the works of the Baroque movement and replaces the royal noblemen and bowls of fruit with a variety of beautiful vehicles. One piece specifically, Momentum, created by artist A.D. Cook, was recently commissioned and premiered at the National Corvette Museum on March 14, 2024. The piece was created as a diptych, one painting in two parts, highlighting the spectrum of the Corvette story, which spans over 70 years. On the left panel, we see the iconic 1953 C1 Corvette, where it all started, with its soft features and instantly recognizable white and red color scheme. On the right is the aggressive and commanding 2023 70th Anniversary C8 Corvette, still sporting white paint but with sharp angles that look dangerous. Pinning these two vehicles directly next to each other, almost overlapping on the canvas, creates a juxtaposition so strong that it demands attention to the shared designs.

Artists who work in realism and hyperrealism have the unique opportunity to create a reality and then subtly and deliberately manipulate reality to make it their own. Sometimes, it can be difficult to recognize that these pieces are painted and created by a human rather than shot with a camera. However, upon further inspection, once your eyes can focus on the details, it becomes clear that this is not a reflection of reality but rather an abstract interpretation of the artist’s world.

Much like the artists who worked in realism and hyperrealism before him, A.D. Cook’s skill and discipline are fully displayed in the Luster exhibition. A.D. hails from sunny Las Vegas, Nevada, where he enjoys being involved with artists and car communities that flourish in the Nevada desert. A.D. is a lifelong lover of the arts and was responsible for all the art seen at the Hollywood Video rental chains across the country. Shortly after that time, A.D. went on to start and run a successful graphic design company with clients all over the world. Over the last several years, A.D. has had the opportunity to focus solely on his passion, hyperrealism art, both with vehicles and human subjects.

I had the opportunity to speak with A.D. recently to understand what it takes to create a hyper-realistic painting and hear more of his personal experiences that eventually led him to create the piece Momentum.

What was the genesis of the Luster exhibition, when did you get involved?

LUSTER exhibit curator David Wagner called me in 2016 and invited me to participate in an exhibit that he was putting together. He said that it would be a two-year tour. In March of 2018 the tour kicked off in Daytona Beach, Florida, and then it just kept growing and growing and growing. David kept calling the artists back, asking, “Can we borrow the art for another year?” Finally, we were all just like, “Let us know when you’re done with them.” That is how it started. Six years later, the tour is still running strong.

LUSTER exhibit curator David Wagner called me in 2016 and invited me to participate in an exhibit that he was putting together. He said that it would be a two-year tour. In March of 2018 the tour kicked off in Daytona Beach, Florida, and then it just kept growing and growing and growing. David kept calling the artists back, asking, “Can we borrow the art for another year?” Finally, we were all just like, “Let us know when you’re done with them.” That is how it started. Six years later, the tour is still running strong. One piece that struck me was America, the painting of the Harley with the American flag on the gas tank. I feel like that must have a story behind it.

One of my collectors owns the Harley-Davidson dealership in Tacoma, Washington, flew me up there to photograph this Captain America chopper because he wanted to sell it, but since it was in his family for so long, he wanted something to remember it by. He asked me to go up there and do a commission artwork. When I finished the painting, I shipped it to him, and about a month later (after David’s call), I called my collector and asked if I could borrow the painting back for a couple of years for the LUSTER Exhibition. He had it in his home for such a short while, so I made him a full-size reproduction so he could still enjoy the painting in its absence.

One of the most exciting parts of hosting this exhibition for us at the National Corvette Museum was unveiling your newest work, MOMENTUM. There is a lot to go over, but I want to start with the beginning. Was this a piece you had wanted to do before Museum Curator David Wagner approached you?

Well, my understanding of the story is that it happened about a year ago when a couple of the Corvette Museum’s staff members were at the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum, saw the Luster exhibit there, and mentioned my motorcycle painting Indian Summer specifically. David [Wagner] called and asked, “Would you like to participate in Luster at the National Corvette Museum?” I am an avid enthusiast and former Corvette owner, so I said, “Oh yeah, absolutely, no doubt!” I was completely excited for teh opportunity and offered carte blanche to create whatever I wanted. As a former muralist, I love to paint large epic pieces so I asked what the largest painting in the show was, and I was told that it was a 96-inch wide piece. I thought the Corvette could not be the second-largest piece in the show, so I opted to create a 48” x 120” diptych.

I like to tell stories through my art, so I wanted to share the story of Corvette’s 70 year evolution and my passion for America’s Sports Car.

I noticed throughout a lot of the paintings in the Luster exhibition that hidden easter eggs seem to be a common theme. Did you hide anything in Momentum?

In Momentum as a whole, definitely. In the left half of the artwork (Creation), there are the Hollywood mountains and beams of light because I drove a Corvette when I painted the Hollywood Video murals and the Pisces constellation above them; that is for me because I am a Pisces, but also because the C1 was created on March 9 (my birthday). The VIN is hidden in the grill, and the Stingray icon is reflected in the windshield, looking forward to Corvette’s future.

On the right side in Evolution, the VIN is hidden in the rear grill and is very small. It’s the Z06’s mirror is a nod to the C1 reflected as the Stingray looks back on its humble beginning. So much is happening in those paintings; the license plate is a painting, and the taillight is a painting. There are a lot of small paintings within those two large paintings. I would have hidden a few more treats if I had another month.

I was going to ask you about that. You mentioned your process when we spoke earlier, and it sounds unique to this painting style. So, individual paintings come together into one, is that right?

I treated it like the taillight was a painting, the grill specifically of the ’53, and then the headlight with its beautiful caged lens. After I was done with each of the cars’ individual components to a point, I covered them with masking tape and paper so I could airbrush each car’s body details in various shades of blues to represent Polo White and Arctic White respectively while protecting my previous work from overspray. After I unwrapped everything, I merged everything together so it doesn’t look like pieces are cut out and taped, and then went over everything with brushes and other tools to bring it all together to create a nice blend of illusion meets reality.

Is that the process for all your paintings? Or was that specific to this one because it was so big?

Yes, when I am going from clean white parts to bold colors like the flag background or the grass, I had to protect the white sections while I was painting the background colors so I did not have to keep painting over the white. That is why I wanted to make the white body panels the last thing I painted so I could take care of any fixes or faux pas before I start doing the blue shading and shadowing.

I am sure this is not a quick process, so how long does it take to complete a painting of this size and scope?

David and I started talking about it a year ago, in the Spring of 2023, and it did not take long for me to say, “Well yeah, I’m on it!” I was stoked to create this artwork. Once I committed, David called back and said, “Let’s do it” after approximately three weeks. Next, I had to find the cars, which meant sourcing a first-generation Corvette. Naturally, the C8s are easier to find, but I wanted a specific 70th Anniversary edition because the story is about Corvette’s creation and evolution.

The C1 was harder to find because they are so rare. I started nay visiting the Cars and Coffee Saturday morning car show here in Las Vegas as I do every so often, and someone told me of a lady named Candice, who owned an award-winning ’53/54 Concours d’Elegance beauty she calls “John Wayne.” I gave her a call, and I was there within an hour looking at her car, which was perfect. Once she committed to it, I had to search for a 2023. She called several people in the Corvette club who offered up their cars, but then, coincidentally, one of my big art collectors here had just taken delivery of a brand new 2023 70th Anniversary Z06 Stingray with carbon fiber wheels.

Now that I had my two Corvettes lined up, I just started drawing, taking a sketch pad, sitting down with a beer, and sketching different ideas. I must have filled at least one or two sketch pads of ideas in figuring out what I wanted to paint to tell my story to tell my story the best way I could. One of those sketches kept popping up in my mind’s eye and eventually became Momentum, two cars celebrating 70 years of iconic legacy. Looking forward, the ’53 is coming to you, and 2023 is going into the future, celebrating the continuing evolution that will excite generations for the next 70 years.

Once I hunkered down, I started preparing my canvases with multiple light layers of gesso, which takes an application a day for a couple of weeks, then wet-sanded for a slate-smooth surface, and sprayed with a nice even white. If you notice up close, you do not see any canvas texture, which allows me to paint finer details.

Once the canvas was ready, Momentum took about three good months to paint, resolving a lot of things, researching tire trends, or the difference between Polo White and Arctic White. Most people do not see all the research that happens in the background of these pieces, but it is hugely important. I had to work through Christmas and New Year’s because I had a deadline for the Exhibit’s debut in March, but it was a total blast, and I am now thinking, “What is the next ‘Vette I get to paint!”

Well, they do not see it unless it is wrong…

So true with any art. Sometimes people see what they wanna see. I occasionally have people point things out in my paintings, and I smile and ask, “Where were you when I painted it!” My paintings are not about copying a photograph. They are inspired pieces of art, and unlike AI, I want my version of the story to come through as well, and celebrate the human experience.

You mentioned that you produced the idea, and then you sketched it out. Right? And then you went and shot the cars? Do you have an idea when you are shooting the cars? Or is it more about getting the angles of the cars and different textures and things? Or is it lining them up in a way that you would want to paint them?

Well, it is a lot of all that and more, like which way the sun is pointed, and where the shadows are going to fall, and shooting at a certain time, because I wanted long shadows, and a good place to shoot the cars, so all of those things need to come together. Then you have two car owners, and this person is available this Saturday, but the other owner is not, so you have to be flexible. It is like a little project just getting everything together, but it was worth it.

To answer your question, I have an idea of how I want it, but I shoot hundreds of reference photos, just in case. When I work with models, I might have a pose in mind, but sometimes, something happens to get to my pre-conceived pose that is more interesting, and I try to be open to ideas that inspire me.

You do a lot of portraits of human subjects. Is it different to paint an organic subject versus something metal and steel?

It is hugely different. Once again, the pieces are compartmentalized on a car. If you are doing realism for any kind, whether it be of car, motorcycle, or anything manufactured, you must adhere to those shapes, unless you are going in a surreal direction, and you are going to exaggerate things intentionally. With a human model, I can ignore or dismiss a tattoo or scar, but with a car, my biggest concern is someone saying, “It’s missing something!” But with either, there is a point where I follow my photo reference, and then I put the photos away and say, “Let’s have fun.” That is where the hidden things come in, where I can twist the story, and people still think it’s a photo.

What struck me about your paintings is that, from a distance, they look like photographs, but up close, you can see all the brush strokes and techniques.

It is chaos if you get close enough. The individual pieces are a bunch of scribbles and brush strokes up close, but step back, and suddenly, everything comes into focus. I think that, whether it is people or cars, I find realism in the abstract and abstract in the realism.

And where did all this start with you personally, how did you end up in the art world?

I knew from an early age that I was an artist. Growing up, I was a construction brat, so I was always the new kid in school, moving two to three times a year between Arizona, Oregon, Colorado, Wisconsin, Illinois, Florida, and a few other states between. There was no rhyme or reason; my dad would say to my mom, brother and sister, “Pack your box; we’re leaving in the morning.” We only got to take what could fit in the box, which meant I lost two violins and half a dozen bicycles. I learned to hold onto my pencils and drawing pads, along with my favorite car magazines to inspire my art. Creating art has been and always will be my life.

Story by Robert Maxhimer © 2024. Shared by permission.

Check out the Corvette 70th Anniversary Art Timeline for the full story of MOMENTUM’s creation.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

- More info

Director of Curatorial Affairs & Education, National Corvette Museum

Robert Maxhimer has oversight of the National Corvette Museum’s collection of historically significant Corvettes and more than 50,000 Corvette artifacts, as well as managing a team of archivists, vehicle maintenance specialists, creators, and exhibit managers to lead the vision and development of Museum exhibits.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

- More info

A.D. is an artist who started drawing at a young age. Throughout his life, he has worked with different creative tools in traditional and digital art and design. His art and writings have been showcased in various publications such as Airbrush Action Magazine, Airbrush Magazine, American Art Collector, Art & Beyond, Dream To Launch, Easyriders, Las Vegas City Life, Las Vegas Weekly, L’Vegue, ModelsMania, Quick Throttle, and The Ultimate Airbrush Handbook.